Jump to:

- Fore-Reef Slope or wall

- Base or Deep Fore-Reef Slope

- Shallow-or-Upper-Reef Slope

- Reef-Crest

- Spur-and-groove formation

- Reef Flat

- Back-reef slope

- Lagoon

- Ironshore

- Tidepool

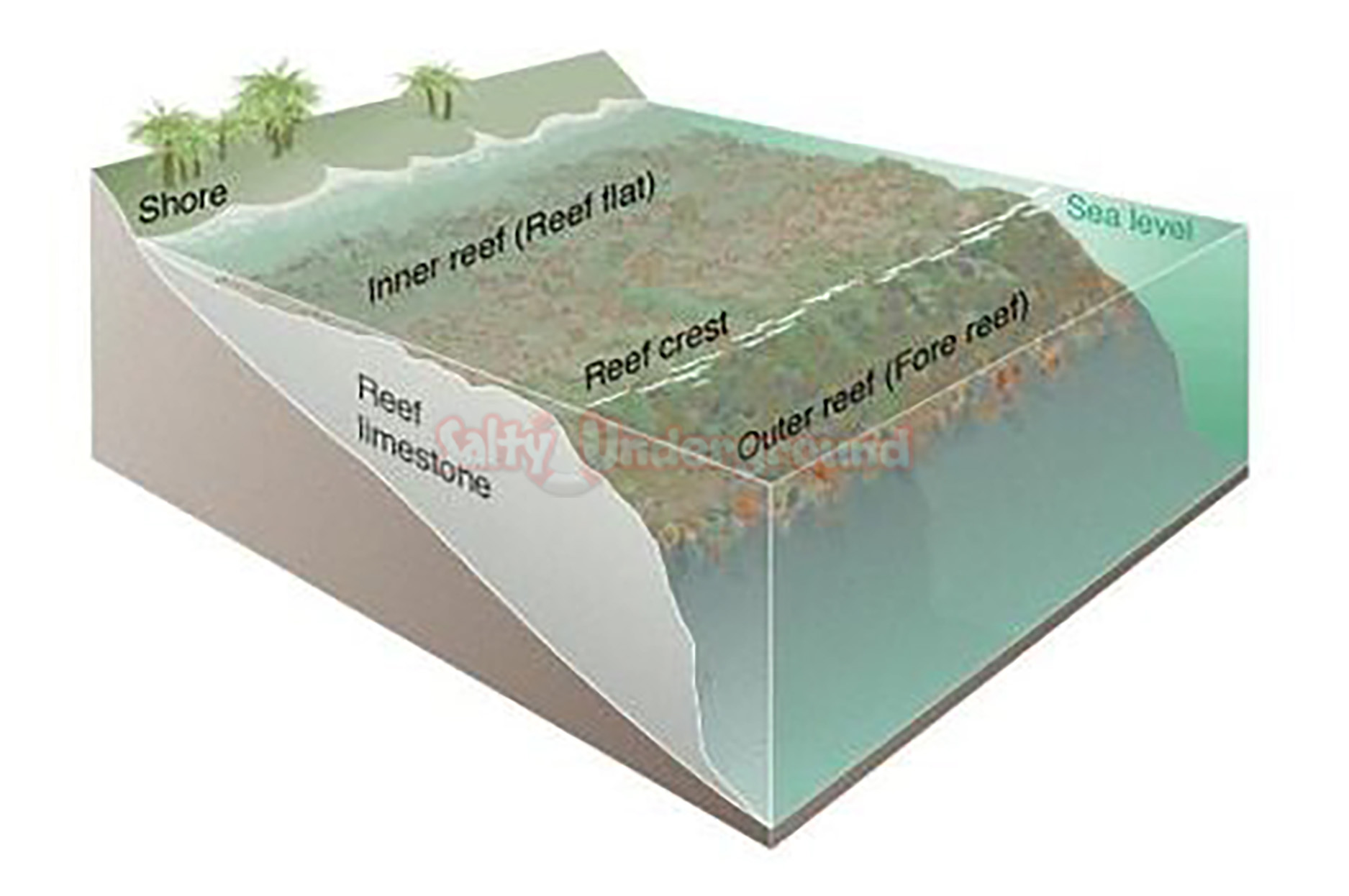

The following is a brief description of the major reef zones. The zones are important because they each have their own distinct pattern of light intensity, water strength and current, amount of detritus, and so forth. Certain corals are especially well suited to particular zones, and will flourish. What this means to the aquarist is that it is important to know which type of zone to mimic in your habitat in order to increase your chances of success.

Fore-reef slope or wall

The fore-reef slope is generally divided into two sections, the base or deep fore-reef slope and the shallow or upper reef slope. The fore-reef slope is basically the vertical portion of the reef which faces the open ocean. It endures the full force of the ocean's waves, currents, and wind. It also enjoys the detritus naturally brought by the current from the ocean floor or along the reef wall.

Base or deep fore-reef slope

The deep fore-reef slope is at the base of the wall where it wells up from the ocean floor. Caves are often cut into the wall, and are more frequent on the windward reefs. It is protected from the harshest of the waves, but conversely enjoys lower light intensity. Typically, you might see nonreef-building corals at the lowest levels, as zooxanthellae of the reef building corals are limited to 100-135 ft. for using light in photosynthesis. Although there is not much light, there is still a lot of life. Nutrients drift down from the high reef zone and settle here, as well as from the ocean current. Sponges and azooxanthellate corals will live in the lower levels of the deep fore-reef and line the inside of the caves. Corals are typically laminar, large, and few in species and number.

Shallow- or upper-reef slope

Shallow-reef slopes are exposed to higher intensity light and stronger water currents. At low tides, portions of the shallow-reef slope may be exposed to air. Although the corals are still not large in number, they are large in diversity of species.

Reef crest

The reef crest is where the waves break over the reef. The water current is strongest here, accompanied by high light intensity, high UV radiation, and air at low tide. Due to the harsh conditions, the corals that survive here are especially hardy, standing up the abusive waves. These are low in species variety, but are some of the most colorful. The corals you will typically find here are the small-polyp, encrusting, and branching corals, as they can survive the harsh water conditions. If the crest is regularly exposed to air, they will desiccate, or dry out. Other, larger-polyped, corals are here in lesser numbers. They will stay moist longer due to their ability to store water. All types will be coated with mucus to prevent drying.

Spur-and-groove formations

This zone is part of the reef crest. As the waves break over the crest, the force of the water creates channels in the corals. There will be a greater diversity of corals, fish, and invertebrates in these grooves.

Reef flat

Reef flats are found to the leeward side of the reef crest. Water is shallow here, and some flats are exposed at low tide. Temperatures vary due to the shallow water, with high temperatures at low tide and cooler temperatures when the time comes back in. The water current is less intense here, as it has been broken by the reef crest. The waves bring in detritus from the open ocean and from the mainland runoff. Salinity can also vary due to strong rains in such shallow water. Despite these swings, corals often thrive here because of the high light intensity, rich nutrients, and gentler water currents. There is a great variety of the types of corals found here; having both fields of soft and stony corals can be successful. Either way, if the reef flat is close enough to the surface to be exposed when the tide is out, the corals will need to depend on mucus coatings and UV protection to prevent desiccation.

Back-reef slope

The back-reef slope is exactly that, the back of the reef wall. This slope is not as dramatic as that of the fore-reef slope. Generally, its depth ranges from 20-60 ft. Because is it protected by the reef crest and the reef flat zones, species diversity begins to increase. Here, massive and hemispherical growth forms are more numerous. Also, the swirling currents help shape the turbinate corals.

Lagoon

Lagoons are found within atolls, and between barrier reefs and the shore. This is shoreward from the back-reef slope, and it levels to a sandy bottom. You will typically see fewer corals interspersed with seagrass beds. The temperature is higher here with lower water flow. Sometimes, there will be patch reefs within the lagoon. The water is nutrient rich and has low visibility. Some corals are known to be particularly tolerant of high-nutrient concentrations or may thrive on the sedimentary bottom.

Ironshore

Ironshores are the rocky shoreline when there is no beach. The waves will pound directly onto the rock, and the amount of coral life is reduced. You will typically see only encrusting or small massive corals clinging to the shoreline, all the way up to the surface of the water.

Tidepool

Tidepools do not have the usual amount of water current found in other reef zones. In fact, they lay waiting for high tides or waves to bring in fresh water and detritus. These are formed on rocky shorelines, as waves wash over them. As there is no fresh current, the salinity, temperature (sometimes over 100˚F), and oxygen levels vary depending on how long the pool has lain stagnant. You may find hardy corals encrusting the sides and bottoms of these pools.