Jump to:

- Introduction

- Balanophyllia

- Dendrophyllia

- Duncanopsammia

- Heteropsammia

- Tubastrea

- Turbinaria

- References

Introduction

Dendrophylliidae corals are some of the most popular and widely recognized LPS (large-polyped stony) corals</a > for the marine hobbyist. Although all stony corals (and even some soft corals) are hermatypic, Dendrophylliidae corals are actually considered to occupy a range of corals which may be reef-building or not, and may be photosynthetic (containing zooxanthellae) or not. Dendrophylliidae corals are commonly called whisker corals, sun corals, orange sun corals, black sun corals, cup corals, orange cup corals, yellow cup corals, pagoda corals, turban corals, scroll corals, and vase corals, depending on their coloration and morphology.

The Dendrophylliidae family of corals are in the order Scleractinia (stony corals) and the subclass Hexacorallia (or also known as Zoantharia). Being in the Hexacorallia subclass means that the polyps have tentacles in multiples of six. Some common genera of Dendrophylliidae are: Balanophyllia, Dendrophyllia, Duncanopsammia, Heteropsammia, Tubastrea, </em >and Turbinaria. This is by no means a complete taxonomy. For more detailed descriptions of each genus, please scroll to the bottom of the page.

Dendrophylliidae corals are found in both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, in tropical and temperate waters, and with or without zooxanthellae. Genera without zooxanthellae, such as Tubastrea, may be found at great depth or in shadowed overhangs, and have been known to colonize deep sea shipwrecks. Because they do not rely on sunlight, but rather on the availability of nutrients, they can thrive in dark waters. However, they will be equally successful in high intensity light if the current it right, as light does not harm them or cause color changes. If this wasn't confusing enough, Dendrophylliidae corals can be colonial, as in the case with Tubinaria, or live as solitary animals, as is the case with both Balanophyllia and Heteropsammia. They may also occupy different growth formations, such as plating, branching, columnar, cup shaped, and foliaceous. In fact, many species of Turbinaria will change shape if you move them to a different habitat.

Many species in this family are considered vulnerable or threatened due to over-collection for the aquarium trade or due to general reef destruction. It is recommended to contact your retailer/wholesaler to determine if the specimen is aquacultured</a >, maricultured, or collected.

Genera

Balanophyllia

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: B. calyculus, B. carinata, B. europaea, B. elegans, B. ponderosa

Common names for Balanophyllia are Balano or cup coral paired with whatever colors the polyp happens to exhibit. Balanos do not contain zooxanthellae. This being said, they can tolerate any intensity of light and must be fed. Many meaty marine food supplements are available, like brine or mysis shrimp. Direct feeding with a pipette seems successful, as is removing to a “feeding dish” to feed the coral separately in order to reduce water pollution. Generally speaking, Balanophyllia corals prefer deep waters of 1,000 meters or more and often in caves or beneath ledges. However, B. europeae, found throughout the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea, is found on ironshores in shallow waters of 50 meters or less. Strong water current is recommended. No matter the species, they are solitary polyps, but you may see daughter polyps bud from the base of the parent polyp. In addition to the asexual reproduction, B. europaea reproduces annually via planulae and is a hermaphrodite. Typically, B. elegans is collected from Australian waters. Polyps can be pink, orange, peach, white, and there are even some reports of blue polyps out of Australia.

Dendrophyllia

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: D. ijimai, D. johnsoni, D. arbuscula, D. californica

Common names for Dendrophyllia are large sun coral or cup coral paired with their color. They do not contain zooxanthellae, and are found worldwide in both tropical and temperate oceans. They are mostly imported from Indonesia. Like the other aposymbiotic corals of Dendrophylliidae, Dendrophyllia spp. can tolerate a range of lighting intensities, prefer strong currents (it brings their food), and must be fed to be successful in the aquarium. Although they can be found in shallow waters, these cup corals can be found up to 3,000 feet (1.000 meters) deep. These sun corals can be cream, yellow, orange, peach, and even a beautiful black. B. johsoni is only found in the Galapagos in two locations: on a seamount (underwater mountain) and off the coast of Santa Cruz Island.

Duncanopsammia

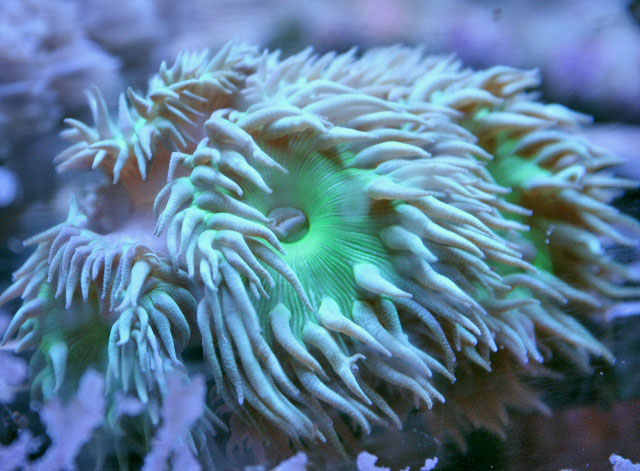

Check our current stock</a >Single Species: D. axifuga

Common names for D. axifuga are Duncans coral and whisker coral. This is considered a near-threatened species by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. It is only found in Australia and Vietnam in the Indo-Pacific Oceans. Whisker corals attach to a hard substrate in sandy or shady areas of the reef at depths of 60-90 feet (20-30 meters). Whisker corals have branching corallites and long tentacles (giving it the “whisker” name). They are normally green, gray, or brownish, with the tentacles often contrasting with the oral disc. Unlike the Dendrophyliidae corals discussed above, Duncans contain zooxanthellae. They do well in low to moderate light and thrive with regular feedings of meaty foods such as brine shrimp. Whisker corals reproduce via budding at the base of the corallite, and may be fragmented for propagation purposes. Corallites are connected at the base by the coenosteum.

Heteropsammia

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: H. cochlea, H. eupsammides, H. michelini

Common names for Heteropsammia are “walking dendro” coral and smooth bum coral. This genus occurs in sandy substrates and houses the commensal worm Aspidosiphon corallicola. It is considered “free-living” as it is not attached to the substrate, and instead moves around by the efforts of this sipunculid worm. There is a hole or holes through the corallum (or skeleton of the polyp) which allows for the worm to feed and move about the substrate. Only the H. cochlea is becoming more common in the aquarium trade and is found throughout Australia, Madagascar, the Red Sea, and Indonesia. More information is needed for the other species in the genus. For success in your reef aquarium, you should have a deep, mature sand bed for both the worm and coral to thrive. Heteropsammia spp. do contain zooxanthellae, but will also benefit from feedings. Another genus, Heterocyathus, will also be found in the same area, and also has a commensal relationship with the sipunculid worm. You can tell them apart by the “smooth bum” appearance of Heteropsammia and the raised “ribs” of Heterocyathus.

Tubastrea

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: T. aurea, T. coccinea, T. diaphana, T. faulkneri, T. micrantha

Common names for Tubastrea spp. are sun coral, cup coral, orange cup coral, and black sun coral. The “cup” refers to the shape of the corallite from which the polyp emerges, and not the shape of the colony itself. Tubastrea corals have branching skeletons, live in colonies, and are aposymbiotic. These must be fed, as they do not have zooxanthellae for photosynthesis. Their corallites are normally covered with bright orange tissue, and the polyps can be yellow, white, or clear. T. diaphana and T. micrantha are darker morphs with greenish-black to brownish black tissue on its coenosteum. T. micrantha typically has dark green or grey polyps while T. diaphana may have blotchy orange and black polyps. As with the other aposymbiotic Dendrophylliidae corals, Tubastrea spp. are normally found in caves or under ledges where strong ocean currents bring food. Trivia: T. coccinea is the only known species to be from shallow waters and found worldwide between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn (referred to as a circumtropical species). T. micrantha has such a sturdy, dense skeleton, it survives typhoons, tropical cyclones, and even nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll!

Turbinaria

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: T. bifrons, T. conspicua, T. frondens, T. heronensis, T. irregularis, T. mesenterina, T. patula, T. peltata, T. radicalis, T. reniformis, T. stellulata</em >

Common names for Turbinaria spp. are yellow cup coral, pagoda coral, turban coral, scroll coral, and vase coral. These are found throughout the Indo-Pacific Oceans and the Red Sea. The common names for Turbinaria corals change with their morphology, and are not necessarily species specific. In all species except T. peltata, the polyps extend only at night.

Like Duncanopsammia sp., Turbinaria spp. contain zooxanthellae. They prefer low to moderate light intensity, but please check with your retailer for care specific to your specimen. Captive bred species are naturally more tolerable of certain conditions. T. peltata, T. patula, and other species of Turbinaria coral can produce copious amounts of mucus. Generally speaking, Turbinaria spp. are hardy corals. The plating and foliaceous growth forms seem to be more difficult than the others to care for; mostly as their requirements for water current may not be met. The colony may adapt a new growth form in response or simply not thrive. Debris should be blown free of the skeleton on a regular basis, especially for the cup or foliaceous forms. These propagate easily through fragmentation and sexual reproduction. Many species of Turbinaria coral are listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as either Near Threatened or worse-Vulnerable. This is mainly due to the general decline of reef health worldwide than a specific threat to any one species. As these are successfully captive bred, why not purchase an aquacultured variety</a >?

References

Borneman, E. (2001). Aquarium Corals: selection, husbandry, and natural history. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H Publications.

Cairns, S.D. (1991). A revision of the ahermatypic Scleractinia of the Galápagos and Cocos Islands.</em > Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 504: 32.

Calfo, A.R. (2002). Book of Coral Propagation: A concise guide to the successful care and culture of coral reef invertebrates </em >(Vol. 1). Monroeville, PA: Reading Trees.

Goffredo, S., Arnone, S., and Zaccanti, F. (2002). Sexual reproduction in the Mediterranean solitary coral Balanophyllia europaea (Scleractinia, Dendrophylliidae).</em > Marine Ecology Progress Series 229: 83-94.

IUCN 2010. (2011). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. Retrieved on August 2nd, 2011, from www.iucnredlist.org</a >

Reef Corals of the Indo-Malaysian Seas. (2011). Marine Species Identification Portal. Retrieved on August 2nd, 2011, from http://species-identification.org</a >

Veron, J.E.N. (2000). Corals of the world. Volumes 1-3. Townsville, Queensland, Australia: Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Wood, E.M. (1983). Reef Corals of the World: Biology and Field Guide. Hong Kong, China: T.F.H. Publications Inc., Ltd.