Jump to:

Introduction

Poritidae corals were once considered to be difficult corals to keep, but advances in the aquarium hobby in the last decade have made these great specimens for reef aquarists. The aquacultured varieties</a > have especially made keeping Poritdae corals much easier due to their more forgiving nature than wild collected specimens. Corals in the Poritidae family are not easily classified for hobbyists. Hobbyists commonly classify the stony coral as either large- or small-polyped stony corals (LPS</a > or SPS). However, members of Poritidae occupy both of those classifications. Although all stony corals (and even some soft corals) are hermatypic, Poritidae corals are the third largest contributor to coral reefs. Poritidae corals are commonly called flower-pot corals, since these are more common in the aquarium trade, but they also include daisy coral, ball coral, finger coral, jeweled coral, boulder coral, Christmas tree worm rock, plating jeweled coral, mustard coral, blue crust coral, thin finger coral, and thick finger coral.

Poritidae corals are in the order Scleractinia (stony corals) and the subclass Hexacorallia (or also known as Zoantharia). Being in the Hexacorallia subclass means that the polyps have tentacles in multiples of six. The genera of Poritidae are: Alveopora, Goniopora, Porites, and Stylaraea. This is by no means a complete taxonomy. For more detailed descriptions of each genus, please scroll to the bottom of the page.

Poritidae corals are polytrophic. They gain their energy from their zooxanthellae (dinoflagellate algae) and from capturing prey such as zooplankton and phytoplankton</a >. They cannot survive on photosynthesis alone. However, that being said, you should not need to directly feed these corals if there is a healthy planktonic population. Then it will be enough to sustain your Poritidae coral. Most agree that brine shrimp and pureed meaty aquarium supplements are still too large for them. Many aquarists have success with a refugium/sump to encourage the growth of plankton. Poritidae corals can then feed on microplankton and nanoplankton, such as phytoplankton and dinoflagellates. If your skimmer or filtration system is too efficient, there are commercial foods available to supplement their diet.

Genera

Alveopora

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: A. allingi, A. catalai, A. daedalea, A. exceli, A. fenestrata, A. gigas, A. japonica, A. marionensis, A. minuta, A. ocellata, A. spongiosa, A. tizardi, A. verrilliana, A. viridis</em >

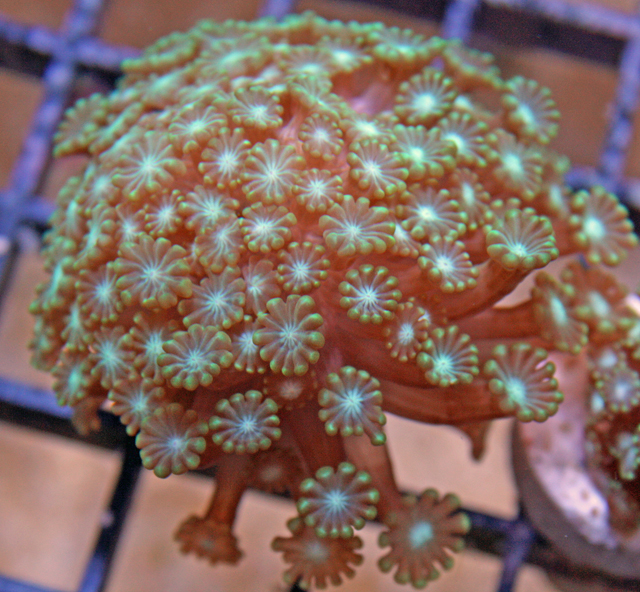

Common names for Alveopora spp. are daisy coral, ball coral, and flowerpot coral. This coral is similar to a Goniopora coral, but it has daisy shaped polyp heads. Its polyps also have 12 tentacle tips, whereas Goniopora corals have 24 tentacle tips. The colony will not be much more that 5 centimeters at the base. It is light-weight compared to other corals due to its porous skeleton. Daisy corals normally have ivory, brown, brownish-pink, or gray polyps with green, yellow, pink, or white tentacles.

Generally speaking, Alveopora spp. are found on reef slopes in turbid water. The murky water likely contains high amounts of plankton</a >, an important food source for Alveopora corals. They are found throughout the Indo-West Pacific. There are currently two species of Alveopora that are considered endangered by the IUCN: A. excelsa and A. minuta. Although Alveopora have been noted to have problems with bleaching as recently as 2007, they have been shown to be quite disease free.

Alveopora corals extend their polyps during the day and are known to be extremely tolerant of a variety of lighting conditions. Clownfish will sometimes adopt an Alveopora coral if there is not an available anemone in the aquarium. However, this may agitate the coral, preventing it from thriving. Alveopora spp. do not need to be directly fed, as they feed on microfauna, such as zooplankton and phytoplankton, in the water. Some aquarists have more success without a skimmer, as it allows more free floating organic matter in the aquarium.

Goniopora

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: G. albiconus, G. burgosi, G. cellulosa, G. ciliatus, G. columna, G. dijiboutiensis, G. eclipsnsis, G. fruticosa, G. lobata, G. minor, G. norfolkensis, G. palmensis, G. pandoraensis, G. pearsoni, G. pendulus, G. planulata, G. polyformis, G. savignyi, G. somaliensis, G. stokesi, G. stutchburyi, G. sultani, G. tenella, G. tenuidens</em >

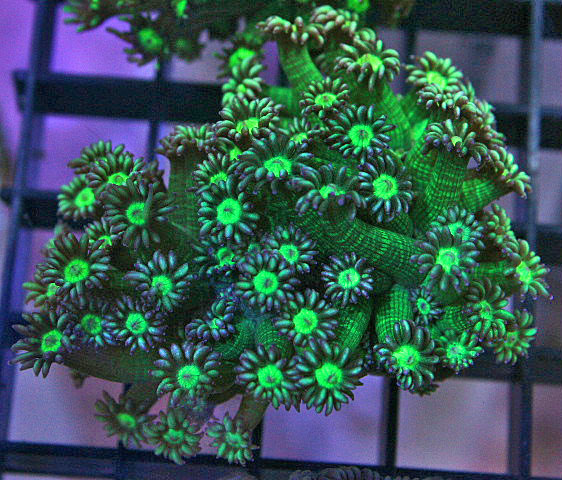

Common names for Goniopora spp. are flowerpot coral, ball coral, and daisy coral. Flowerpot corals have extremely long polyps, sometimes up to 12 inches. These look similar to Alveopora spp.,but Goniopora spp. have 24 tentacles while Alveopora spp. have only 12. By day, the polyps will be completely extended, and will typically be retracted in whole or part at night. They usually are columnar and massive, and rarely do they branch. They can come in a variety of colors, being green and brown (the most common) or pink, yellow, gray, and cream colored. Some aquacultured</a > varieties have shown deep burgundy colors.

Goniopora spp. prefer calmer waters, which explains their prevalence in lagoons, reef flats, rubble zones, and other shallow areas. They are also common in turbid waters on reef slopes. This is ideal for bringing phytoplankton</a > to the coral. Give flowerpot corals space in your reef aquarium. Their long polyps (as mentioned up to 12 inches) may sting neighboring corals. Once out of reach of the polyps, your other specimens should be considered safe.

Porites

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: P. astreoides, P. branneri, P. colonensis, P. compressa, P. cylindrica, P. divaricata, P. furcata, P. lichen, P. lobata, P. lutea, P. pukoensis, P. rus, P. solida</em >

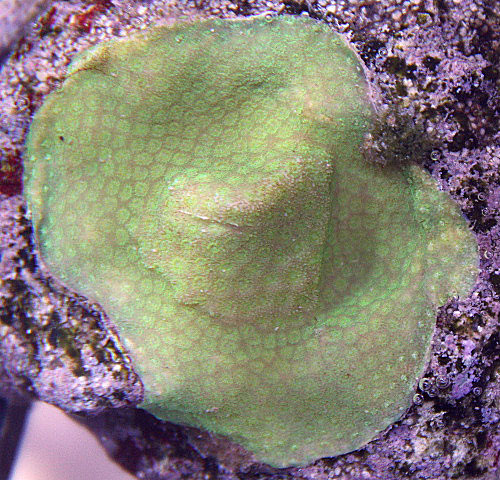

Common names for Porites spp. are finger coral, jeweled coral, boulder coral, Christmas tree worm rock, plating jeweled coral, mustard coral, blue crust coral, thin finger coral, and thick finger coral. These appear very different from Alveopora and Goniorpora corals because they lack the long, flower like polyps. However, they still have the porous skeletons typical of the Poritidae family. Porites corals typically grow as encrusting, branching, massive, lobed, or plating. In fact, some Porites spp. colonies are the largest massive coral colonies discovered. Finger corals can be a bright lime green, pink, blue, yellow, purple, or even a mustard color.

Porites spp. will regularly shed an outer mucus layer. This is natural, and should not concern you. This is a method that these and other corals have developed to remove waste and algae from their surface. These corals normally prefer high light intensity, but are adaptable. Although Porites sp. are quite common in the wild, captive bred Porites sp. are hardier than the wild collected varieties</a >. These are normally found on upper reef slopes and reef flats.

Stylaraea

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: S. punctata

There is no common name for Stylaraea spp. It is unlikely you will find Stylaraea corals in the aquarium trade. They are rarely spotted by collectors or even by marine biological surveys. This is the smallest of the zooxanthellate corals (they contain symbiotic dinoflagellate algae). These are colonial, and their colonies are normally less than 1cm in diameter and hardly ever larger than 2cm. The individual polyps and corallites are less than 1 millimeter across. No wonder people miss it!

Stylaraea spp. are a pale brown or purple in color. Like Porites, they have small calices and polyps. They have been found in the Red Sea, the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and in the Gulf of Aden. These are found in subtidal zones, the part of the sea shore that is only exposed at extreme low tides like at full and new moons. This is shallow water, not much more that ½ a meter deep. Stylaraea corals are normally found in the shadows of dead corals or massive coralline algae</a >.

References

Borneman, E. (2001). Aquarium Corals: selection, husbandry, and natural history. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H Publications.

Calfo, A.R. (2002). Book of Coral Propagation: A concise guide to the successful care and culture of coral reef invertebrates </em >(Vol. 1). Monroeville, PA: Reading Trees.

IUCN 2010. (2011). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. Retrieved on August 11th, 2011, from http://www.iucnredlist.org</a >

MaClanahan, T.R., Atteweberhan, M., Graham, N.A.J., Wilson, S.K., Ruiz Sebastian, C., Guillaume, M.M.M., Bruggeman, & J.H. (2007). Western Indian Ocean coral communities: bleaching responses and susceptibility to extinction. Marine Ecology Progress Series 337: 1-13.

Reef Corals of the Indo-Malaysian Seas. (2011). Marine Species Identification Portal</em >. Retrieved on August 11th, 2011, from http://species-identification.org</a >

Veron, J.E.N. (2000). Corals of the world. Volumes 1-3. Townsville, Queensland, Australia: Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Wood, E.M. (1983). Reef Corals of the World: Biology and Field Guide. Hong Kong, China: T.F.H. Publications Inc., Ltd.