Jump to:

Introduction

Pulse corals are found in the Subclass Octocorallia, Order Alcyonacea, Suborder Alcyoniina, and Family Xeniidae. The corals found in Xeniidae are called pulse corals, due to the pulsatile motion of their polyps.

Like all octocorals, pulse corals have eight tentacles and eight mesentaries on their polyps. They lack the skeletons of the stony corals, but some pulse corals may have sclerites, small calcite pieces set throughout their bodies. They all contain zooxanthellae, meaning they are symbiotic, and are non-reef building (non-hermatpic). Pulse corals, Xeniidae, are set apart from the other octocorals by their ability to pulse their polyps rhythmically. Typicaly, Xeniidae have a stalk and branches. Anthelia spp. however, do not branch and rarely pulse. Instead, their polyps grow from an encrusting mat. All genera, however, possess “feathery” polyps. They can be white, yellow, green, blue, and brown. Some hobbyists have reported other colors in captivity.

Xeniidae corals heavily rely on their zooxanthellae, but they still rely on other food sources. They will capture prey, just like the stony corals, but they feed on much smaller forms of plankton, like phytoplankton, nanoplankton, and bacterioplankton. Because of their shape, they don't capture prey, they absorb them! The do not have many nematocysts. Instead, their tentacles have microvilli covering their epidermal layer which are great for absorbing nutrients. Because of their particular feeding habits, it isn't necessary to directly feed pulse corals. The zooxanthellae provide nutrients via photosynthesis, and the polyps will absorb dissolved organic matter directly from the water. At Salty Underground, we've found some pulse corals will thrive in the absence of a skimmer. This allows more free floating nutrients to stay in the water.

For the pulse corals, they can have two specialized polyps, autozooids (the feeding polyps) and siphonozoids (polyps responsible for water circulation). If the coral only has autozoids, they are commonly called monomorphic. A few genera of the pulse corals have both types of polyps, and they are referred to as dimorphic. Solenia, canals within the coral, connect the various polyps and foster movement of nutrients.

Xeniidae corals are among the most fruitful families of corals. They will propagate via the “normal” means of budding and fission. In addition, they will expel planulae (swimming larva). An interesting mode of reproduction is how the xeniids will “walk”. Some will detach and reattach their stalks and branches in search of a better location. As a result, pieces will be left behind in their “footprints” and grow a daughter colony. Some aquarists have reported new colonies growing from detached polyps. For example, a colony may expel a polyp due to stress, or a hobbyist may clip polyps from a dying stalk in the hopes of saving it. These can settle, reattach to the substrate, and thrive again.

Aquacultured</a > pulse corals are particularly hardy and are ideal for a beginner</a > aquarist. These can grow quickly and in a variety of water conditions. Some reports indicate Xeniidae spp. will grow in polluted waters near resorts. If a reef has been damaged, pulse corals are some of the first species to repopulate the reef. There are some precautions to be taken, however. When stressed, Xeniids will produce large amounts of mucus. Wild collected species of xeniid do not have as high a survival rate as captive bred specimens. It is posited that this is due to the increase in waste, ammonia, and bacteria that accumulate during shipping. If your pulse coral has a heavy layer of mucus, a strong water current helps them shed it, as well as any other debris, like algae. Lighting conditions vary by species, but usually, if it is an aquacultured specimen, xeniids will thrive in moderate to high light intensity. Several sources have also mentioned that Xeniidae corals do well when coupled with Sarcophyton spp</a ></em >. (a genus of leather coral).

Genera

Anthelia

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: A. flava, A. Fishelsoni, A. glauca

Common names for Anthelia spp. are glove coral, pulse coral, and waving-hand coral. As mentioned earlier, Anthelia corals are different morphologically than other Xeniids. They lack the common stalk and branches. Instead, their polyps grow directly from an encrusting mat. They are monomorphic, containing only autozooids on their polyps, which cannot retract. There are conflicting reports on whether Anthelia spp. exhibit pulsing behavior. Anthelia corals typically are white, gray, or brown, though A. flava is blue.

If you purchase captive bred varieties of Anthelia spp., you will have better luck than with wild collected species. They are normally non-toxic, and peaceful. Other corals can outcompete with them for space. Captive bred specimens seem to thrive in moderate to bright lighting in a moderate current. A good rule of thumb is if an Anthelia coral is brightly colored, it needs a higher intensity light. A. glauca is from deeper water, and needs lower intensity light. These corals do not need to be directly fed.

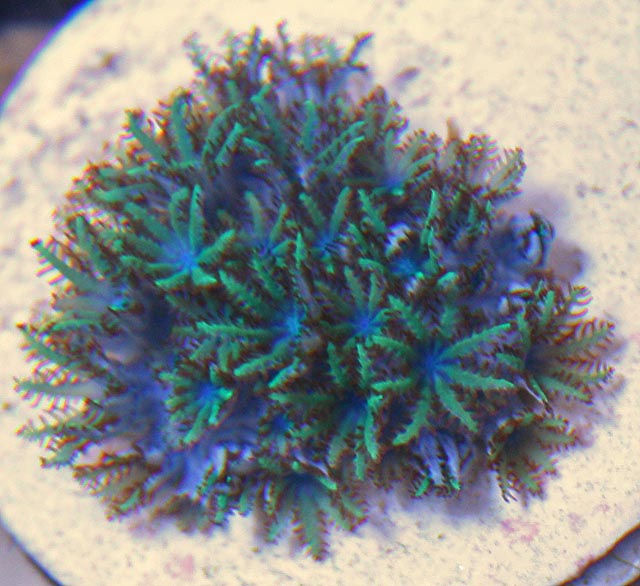

Cespitularia

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: C. infirmata

There are no common names for Cespitularia corals. This genus is less common in the wild. These colonies have stalks and branches. Their polyps, like Anthelia spp. are monomorphic and non-retractile. Cespitularia polyps mostly grow from their branches, but will occasionally emerge from their stalks.

Make sure to do your research on your Cespitularia coral, as many are quite toxic toward other corals. These are less commonly available due to their high mortality rate in shipping. It is recommended for you to find and aquacultured variety. Cespitularia spp. prefer turbid water of moderate current and light intensity.

Efflatounaria

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: E. infirmata

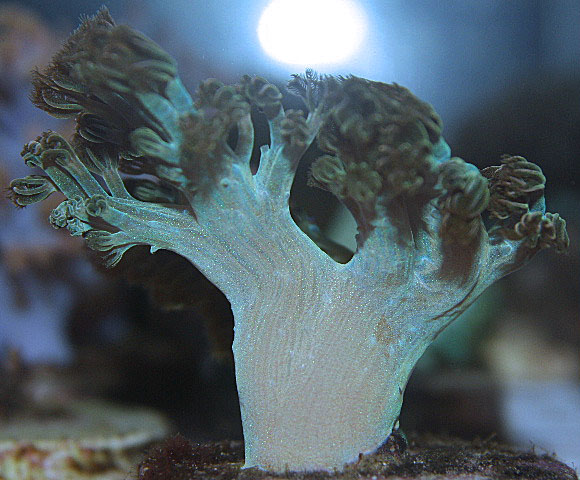

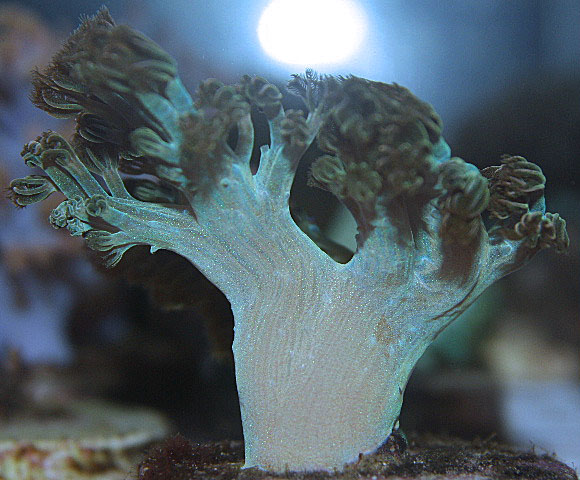

There are no common names for Efflatounaria corals. Like Anthelia and Cespitularia corals, Efflatounaria corals are monomorphic, containing only autozooids. Unlike them, Efflatounaria spp. have a sterile (containing no polyps) stalk before branching. These polyps are retractile, as well. The stalks are typically white with polyps usually of contrasting colors in brown, green, blue, or yellow.

Efflatounaria corals are naturally found on fore-reef slopes. As such, they thrive with high currents, clear water, and high light intensity. Some are toxic to other reef organisms, so make sure to research the species you are interested in before adding to your aquarium. They will reproduce in captivity via fission, forming daughter colonies via stolon (runners from their polyps), and sexual reproduction. They are not commonly imported. It is recommended you find a captive bred</a > variety.

Funginus

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: F. heimi

Orignally called Fungulus spp., a replacement generic name was proposed in 1987, of Funginus, as Fungulus had been in use since 1888 for a tunicate (a filter feeder like a sea squirt). These are rarely found in the wild. Records indicate they have been found in New Caledonia, the Ryuku Islands, and the Great Barrier Reef. More information is needed in this genus.

Heteroxenia

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: H. fescescens

Common names for Heteroxenia spp. are pulse coral, pom-pom coral, and also pom-pom xenia. Heteroxenia spp. are dimorphich, containing both autozooid and siphonozoid polyps. Their stalks terminal in a capitulum (a mushroom shaped top) from which the polyps emerge. The tentacles on the autozoid polyps extend in a way that resembles a pom-pom of a cheerleader, hence the common name. These stalks rarely branch. Heteroxenia corals are usually light in color, white or cream. Their polyps pulse faster than other Xeniids.

Found commonly on inner reefs in shallow zones, they prefer high light intensity. Due to their prevalence in shallower waters, they may be exposed to air during low tide. It is not necessary to directly feed this coral. They will receive all their nutrients from their zooxanthellae and from absorbing microfauna in the water.

These are prime specimens for captive breeding. Their planulae (larva) brood first in their gastrovascular cavity before they move on to pouches in their mesoglea (stiff, gelatinous, connective tissue with lots of air space reminiscent of stale Jell-O). After their planulae are released, they quickly settle on a substrate, metamorphosis into a sessile coral, acquire zooxanthellae, and mature into polyp. For H. fuscescens, this all happens in a month's time. Heteroxenia corals have a high mortality rate in collection and shipping. It is recommended to find an aquacultured</a > variety.

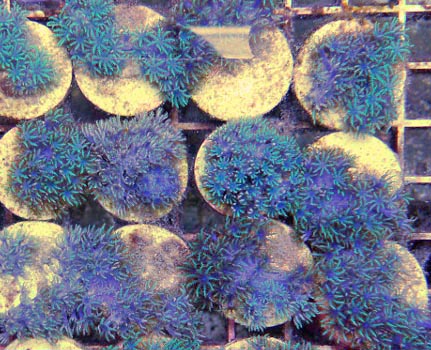

Sympodium

Check our current stock</a >

Sympodium spp. are less common in imports, and are usually seen coming from Indonesian reefs. It has rarely been observed to pulse. They are more colorful than other Xeniids, with contrasting stalks and polyps; some color varieties have green or blue polyps and red tentacles (pinnules) or blue stalks with blue polyps and green tentacles. Others seem to be monochrome, but still brightly colored. They seem to do adapt well to any lighting, and prefer moderate current. Their stalks branch, much like Xenia corals. More information is needed on this genus.

Xenia

Check our current stock</a >Common Species: X. mucosa, X. elongate, X. stellifera, X. macrospiculata, X. multipnnata, X. embellata</em >

A common name for Xenia corals is pulse coral. Like Heteroxenia, Xenia corals have a stalk and capitulum, from which the polyps emerge. Their stalks are usually unbranching and white or cream in color. Their non-retractile polyps are commonly not of contrasting color, being cream, white, gray, light brown or light green.

Xenia corals are very hardy in the wild, growing in some polluted areas or on damaged reefs. They grow basically wherever they want to-they just “walk” there. By detaching and reattaching their stalks and polyps, they will move their colony to a more desirable location. They can also detach and float freely as an anemone does, until it finds a more suitable location. They are a very fast growing and competitive species and will sometimes encrust over other corals. Some can be toxic to stony corals as well, so be careful with you placement of Xenia spp. in your aquarium. Some crustaceans, nudibranchs, and worms will feast on Xenia corals, so please make sure all of your animals can cohabitate before adding Xenia to your aquarium. Xenia spp. do well in captivity, and captive propagation has been successful. They have a high mortality rate for collection from the wild with high transit times. It is recommended you find an aqualcultured</a > specimen. X. umbelata will brood its planulae (larvae) in pouches prior to release, even endowing them with zooxanthellae before hand. They also propagate through fission and leaving behind daughter colonies while they “walk”.

References

Alderslade, P. (2000). Four new general of soft corals (Coelenterata: Octocarallia) with notes on the classification of some established taxa</em >. Zool. Med. Leiden 74 (16), 15.ix.2000: 237-249.

Borneman, E. (2001). Aquarium Corals: selection, husbandry, and natural history. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H Publications.

Calfo, A.R. (2002). Book of Coral Propagation: A concise guide to the successful care and culture of coral reef invertebrates (Vol. 1)</em >. Monroeville, PA: Reading Trees.